Innovation to commercialisation: Atherton Bikes and the journey of an SME bringing AM production in house

Bringing Additive Manufacturing in house is a big step for any company, but when you are at the small end of the ‘SME’ spectrum, it can be an especially bold move. Robin Weston recently visited Atherton Bikes, based in rural west Wales, to see how this specialist bike producer is enjoying ramping up in-house production of its titanium and carbon fibre performance mountain bikes on a new, four-laser Powder Bed Fusion (PBF-LB) machine from Renishaw. [First published in Metal AM Vol. 8 No. 1, Spring 2022 | 10 minute read | View on Issuu | Download PDF]

Metal Additive Manufacturing is expensive, demanding and out of reach of ‘normal’ companies. “What?! Now you tell me,” I hear you cry. I speak as someone with over fifteen years of experience ‘sweating the numbers’ as a product manager in AM machines and it is often, although not always, the justification for the first machine’s purchase that seems to cause the most pain. It gets easier to make the numbers work once multiple machines are installed. Better economies of scale, division of labour, more efficient utilisation, etc. Even then, there must be a compelling reason to invest, whether that’s performance materials, complex geometries, part consolidation, customisation, or any combination of reasons to go down the AM route.

When Atherton first started using metal AM for its competition bikes, the project fell right into the AM ‘Goldilocks zone’. The technical case was solid: titanium material – tick, demanding and unique geometry – tick, and customisation – tick.

In my previous article in the Autumn 2020 (Vol. 6 No. 3) issue of Metal AM magazine, we took a deep dive into Atherton’s journey from a family of world-class, world cup-winning mountain bike riders to a company of ambitious bike manufacturers and adopters of new manufacturing technologies and approaches. However, at this point, the Atherton team didn’t own an AM machine: components were supplied as part of a machine vendor project to demonstrate the viability and usefulness of metal AM in an open-access project, to showcase AM in performance sports equipment and, in so doing, attract others who could see parallels with their projects and businesses.

Atherton was working with its first fifty customers at the same time as honing the race team’s prototypes, learnings from which fed directly and almost immediately into the production models.

After a recent visit to Atherton to get updated on how things are progressing, much has changed. The company now has its own metal AM machine on site and has recruited a team of engineers to develop and support its in-house manufacturing processes, all housed in a new (to Atherton) factory, just down the road from the Dyfi Bike Park. Coupled with this is a healthy order book and commercial bike supply is now well underway, with extremely positive bike industry reviews of the commercial machines coming in that further support the Atherton approach.

Evaluating the options: subcontracting AM production versus bringing it in house

So, what are the advantages behind the major step of bringing AM part production capabilities in house, rather than developing a commercial supply partner to take over from a machine vendor? The latter option is the relatively low-risk approach, with smaller companies often initially working with machine vendors to develop some knowledge, before engaging with a commercial subcontractor, which then produces the matured component design to the exact customer specifications.

Whilst outsourcing is often the path of least resistance and, with the right supplier, a successful supply partnership suits many companies, it demands a detailed approach to capturing engineering data; there are potentially more variables in AM than other manufacturing processes, especially when configuring builds.

For efficiency, many subcontractors will want to fully populate each machine run, unless otherwise agreed. If your parts are nested with other components for other customers, any changes to how each build runs can impact part variability. Defining the exact processing conditions for your parts should therefore be part of your terms of supply, but you might expect to pay a little more to dictate such terms. It’s not just the geometry that’s important, but where the parts are placed, how the fusing energy is applied, how the support structures and part orientation affect the post-processing and final finishing of the components and, ultimately, the overall result. There is an increasing abundance of suppliers who provide AM manufacturing services. Many are well versed in the demands of high-quality production manufacturing and also run precision post-processing technologies to offer a complete service.

The alternative approach is to bring metal AM technology in house and much of the decision here depends on a company’s appetite and ability to raise capital investment and to recruit and develop the skills required to become an AM manufacturing expert. Anyone who has researched the latest multi-beam, productive metal AM systems will know that the capital required runs well into seven figures, whether that’s in dollars, euros or British pounds. There is also much to consider about the factory environment, skills and post-processing technologies required.

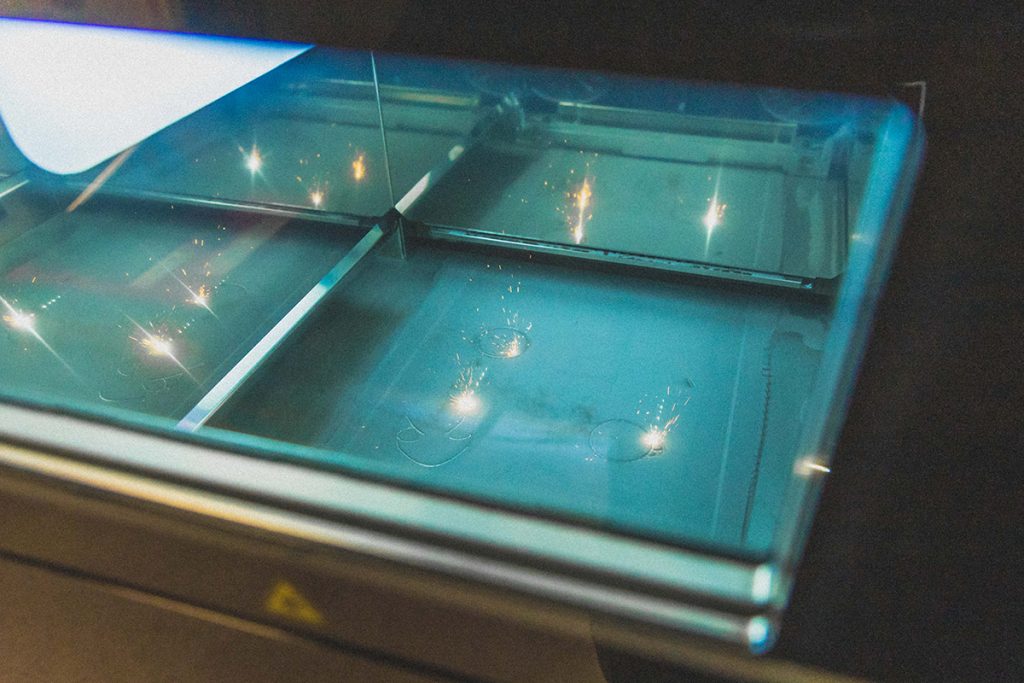

When I visited the Atherton factory, it had just installed its new metal AM machine. It’s hard to overstate what a bold move this is for a young, dynamic and pioneering SME. Although I recognise that multi-laser metal AM machines are becoming the norm these days, it’s only a few years since this advance in the technology actually emerged.

Getting to grips with optimising a machine’s performance is not without its challenges. Hearing the Atherton engineers talking in detail about how they use ‘swim lanes’ to manage process emissions and the interactions between the multiple beams on the company’s Renishaw RenAM 500Q machine, clearly shows that process knowledge is key to success. Having this capability in house means decisions about how parts are designed and nested are informed by an understanding of the manufacturing process that onlt grows over time.

Whilst I know one can achieve this in partnership with a component supply chain partner, it does reveal the additional dimensions that might not be apparent without direct experience of running an AM system. It is also clear that part production volume also helps populate builds more efficiently. Whilst is possible to produce a single frameset on in one machine cycle, something that takes around sixteen hours for a single frame, it turns out that because it’s possible to produce approximately 1.3 framesets on a single substrate, the most efficient use of the machine is to make batches of component families. This also overcomes the other variable of inefficient laser use due to the differing heights of components.

hen producing a complete frameset in one build, the taller parts keep building after the shorter pieces are finished; while some AM machines can use all lasers on the remaining taller parts, this is potentially inefficient and risks differing thermal histories in the latter regions of the components, which may affect part variability and metallurgy.

The skills factor

From talking to the team, it’s evident that skills play a crucial part in developing in-house capability. With Atherton, based out in the relative wilds of rural Wales, the question of recruitment and attracting the right skills and capabilities was a concern. Passion is key and it’s evident that the outdoor extreme sports environment plays a big part in attracting talent. When compared to alternative career paths in large corporate firms, working with the Atherton team is much more like working in F1, with the bonus chance for every staff member to throw themselves off a mountain top on one of the company’s products, should the mood take them. I’m sure the HR department comes to work on Monday with some trepidation, though!

As anyone experienced in metal AM will also attest, passion is vital if a company is to meet the challenges of making successful AM parts. There are steep learning curves to climb and, particularly for the Atherton team, the challenge of fitting the Renishaw machine into a relatively modest (but admittedly rather cool) facility.

Preparing the environment for the machine included an appropriately specified environment for the AM machine and ancillaries. This includes environmental air handling equipment due to the small space available, storage for processing gas, changes to the floor to support the machine load, and providing suitable isolation from potential vibrations from passing trains on the nearby railway line. From selecting and defining a metal powder supply chain and ensuring the specifications are consistently achieved, to dealing with waste filters from the process gas, there is much to consider when running a metal AM machine in house.

Make or buy (innovate or die)

Is it worth the effort? Wouldn’t it just be easier to send the geometry out to suppliers for the most competitive quote? True, it looks like it might be on paper, but that misses the point. When aiming for excellence, part of the process is to be empowered to explore the performance envelope of your production capabilities fully. If you subcontract, how do you know what you are getting is as good as it can be? Are there opportunities you could be missing to improve your product or innovate? Many bike manufacturers are commoditised, with only a few companies truly innovating. Many well-known brands are using the same supply chains and, whilst these companies can make capable advanced products by this route, the innovation pathway is thus limited for the most high-end products.

Anyone who follows elite sport or competition in whichever discipline will recognise that, even though the equipment used by the athletes looks like the kit you can buy in the shops, the reality is that the competition product is honed to be the very best of its type. It’s hard to offer this level of performance to the public at an accessible price point. The Atherton team’s ambition is to overcome this. Whilst Atherton machines at their peak factory race team specification will command a hefty five-figure sum for the highest group-set specification, the entry-level product is priced to be accessible to those dedicated to their chosen sport. The frame itself is the most stable element of the overall bike cost and a well-set up entry-level product in the Atherton range will be a revelation to most riders. If you want even more performance, it’s a matter of increasing your component budget or as well as exploring the twenty or so frame options that Atherton offers.

Safety in numbers

Atherton is not alone in the pioneering use of advanced AM technologies in bike production and there is clear potential for metal AM applications beyond the frame itself. The golden rule is to avoid using metal AM just because you can; the technical demands of the component must lead the choice. If an alternative process can do a better job, then use it. The obvious advantage of access to your own metal AM system is the opportunity for experimentation that it permits; this is where future innovations will be born.

As for production parts, once a design is stable and the process variables are understood, it’s possible to have a blend of in-house supply combined with a capable subcontract supply chain to support production demand fluctuations.

We will continue to watch Atherton’s AM journey with interest. Having visited this passionate, young and dynamic team, it’s clear that all the ingredients for continued success are very evident. So, keep up the metal bashing!

Author

Robin Weston

Cheshire, United Kingdom

[email protected]

Atherton Bikes

For more information on Atherton Bikes and to order Atherton Bikes online visit www.athertonbikes.com