Design for Additive Manufacturing: A workflow for a metal AM heat exchanger using nTopology

Heat exchangers have become – excuse the pun – a hot topic in metal Additive Manufacturing. This is an application that can, in one go, leverage advances in equation-driven CAD design software and the capabilities of AM to produce geometries that would be impossible by any other manufacturing process. Olaf Diegel , Wohlers Associates, reports on a project exploring workflows for AM heat exchanger design using design tools from nTopology. [First published in Metal AM Vol. 7 No. 2, Summer 2021 | 10 minute read | View on Issuu | Download PDF]

With the growing maturity of metal AM, new approaches to design software have been optimised for complex lattice structures. Conventional CAD software can be used, but users may experience difficulty in dealing with large arrays due to the required processing power. New software approaches are overcoming this challenge by handling features as equations rather than as solid bodies. For example, a large lattice can be processed similarly to a single feature. A few extra numbers are added in the equation, telling the program how many times to repeat the pattern in each direction. This equation-driven approach makes it easier to design products with large, complex lattice structures, textures and features.

Without this new breed of software, it would be difficult – if not impossible – to design these complex shapes. Also, a heat exchanger using gyroid structures would be impossible to produce without AM.

Heat exchangers and the gyroid revolution

A heat exchanger is a system used to transfer heat between two or more media. It allows heat from one substance, usually a liquid or gas, to pass to a second liquid or gas. The device is used to cool hot areas of a system, or vice versa. The two media do not mix or come into direct contact with one another. Heat exchangers are commonly used in both cooling and heating processes for a wide range of industrial applications, such as refrigerators, furnaces, air conditioning systems, transportation, oil refineries, commercial environments, and hospitals.

Historically, ‘plate and frame’ heat exchangers were made by forming plates into a labyrinth of channels. The plates were then laminated to create a network of hot and cold channels to transfer heat from one medium to the other. The other main conventional manufacturing option has been ‘shell and tube’ heat exchangers. This type combines thermally conductive tubes and plates used to transfer heat from air-to-air, water-to-water, or air-to-water-to-steam.

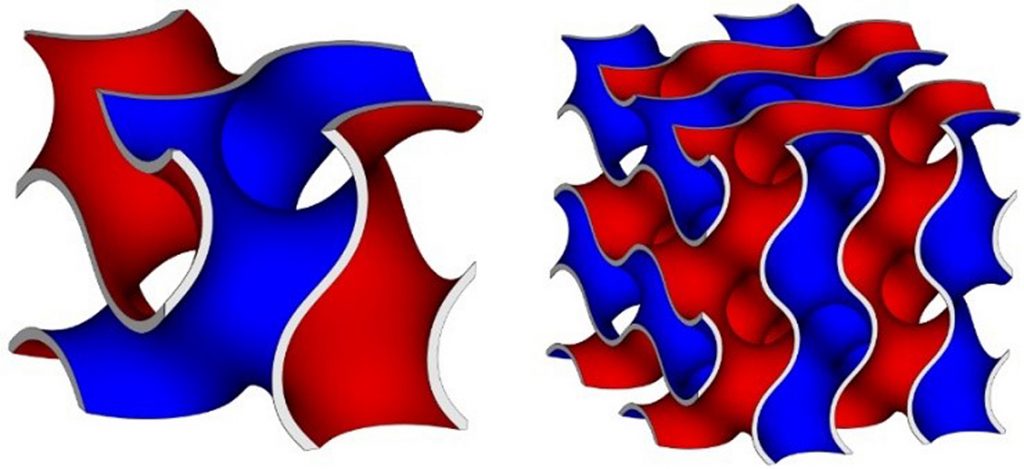

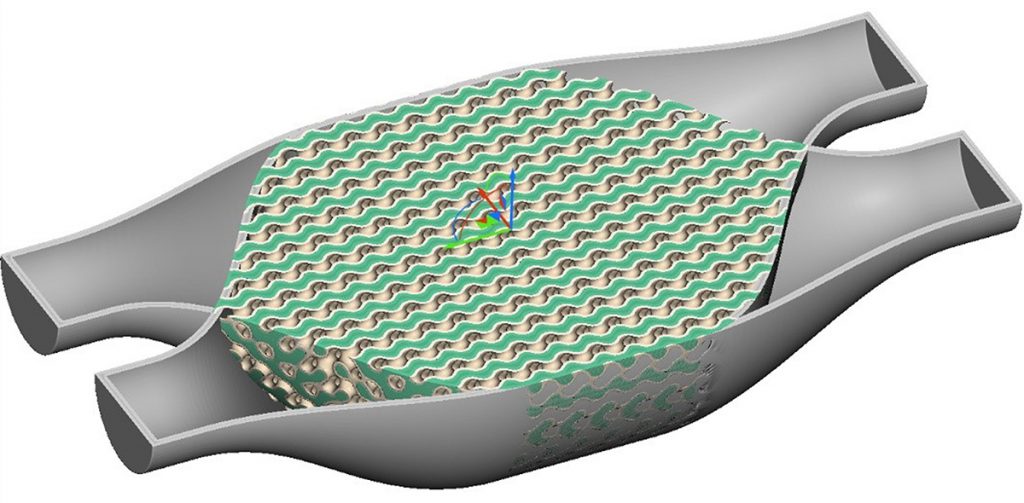

A gyroid is part of a family of triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS), discovered by Alan Schoen in 1970. It separates space into two oppositely congruent labyrinths of passages that have no lines of reflectional symmetry. In the context of heat exchangers, gyroids have two distinct advantages: they offer a large surface area for heat dissipation and cause significant turbulence, increasing the Reynolds number, which improves heat dissipation. In the context of metal AM, they have a distinct advantage of being self-supporting. Even at relatively large sizes, these structures can be additively manufactured without the need for support material. These advantages make gyroids a good candidate for creating more efficient heat exchangers.

Designing a gyroid heat exchanger

This project began as an exercise in understanding the capabilities of new equation-driven CAD design software – in this case, nTopology. As an example, a compact heat exchanger was designed for a conformal water channel cooling system for a pellet extruder.

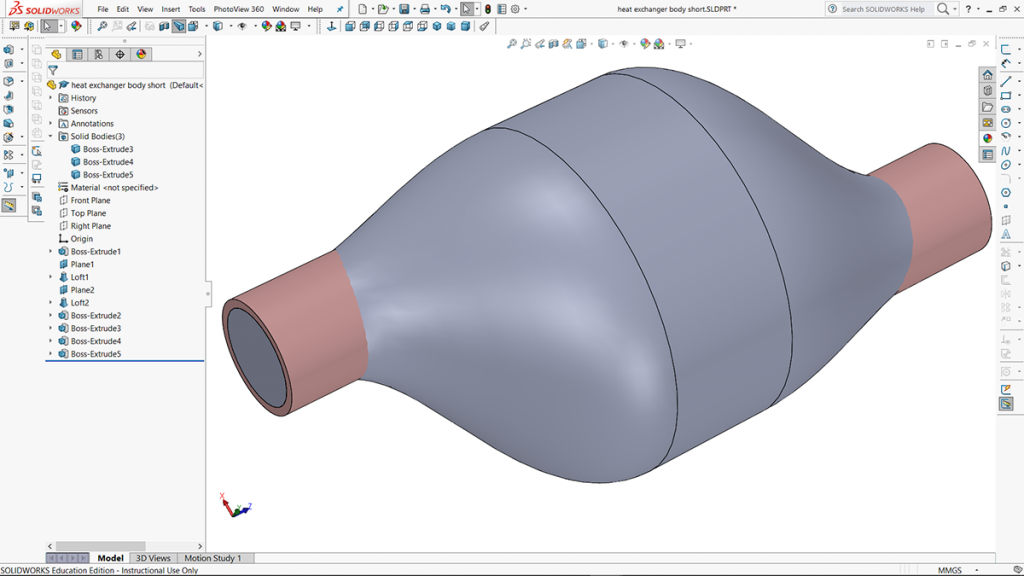

The process begins with designing the physical structure of the heat exchanger using Solidworks. New equation-driven CAD software products are capable of basic geometric features, but they are not as advanced as conventional CAD software.

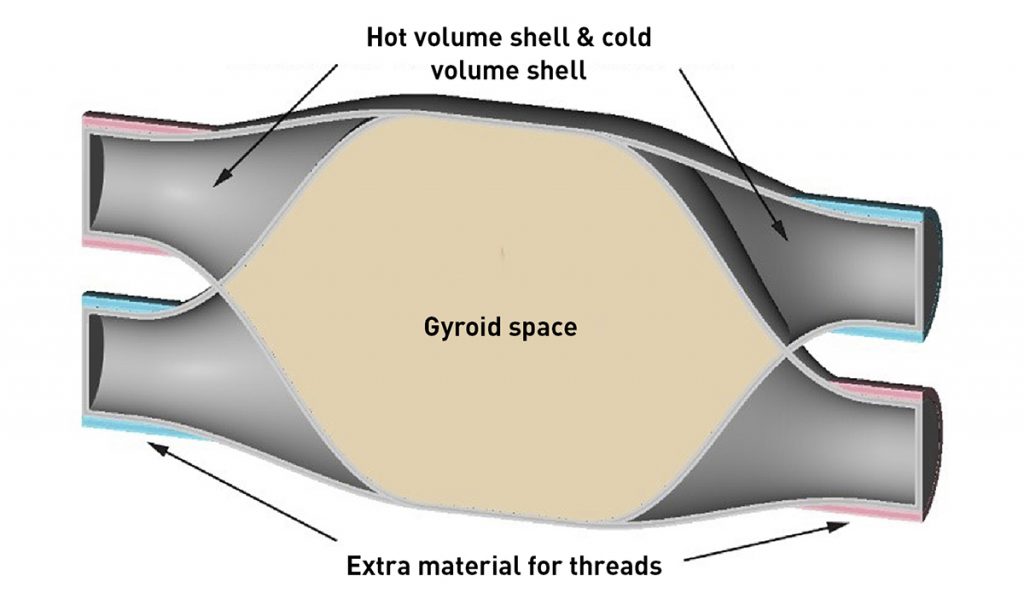

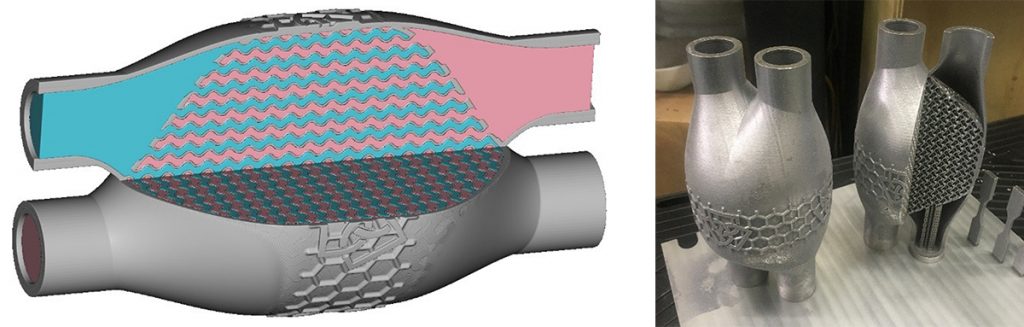

For this heat exchanger design, one side was modelled and then mirrored to produce the desired shape. The part was imported into the nTopology lattice design software. From this point, core bodies were created to make up the various parts of the heat exchanger. They included the cold and hot channel outer shells, the intersecting volume that would later become the gyroid space, and a few extra bodies, such as the extra material required at the inlets and outlets for threads, logos, and more. The overall logic is to create all the subcomponents as separate units, called blocks, using nTopology. A range of Boolean operations (i.e., unite, intersect, and subtract) were used to combine the subcomponents.

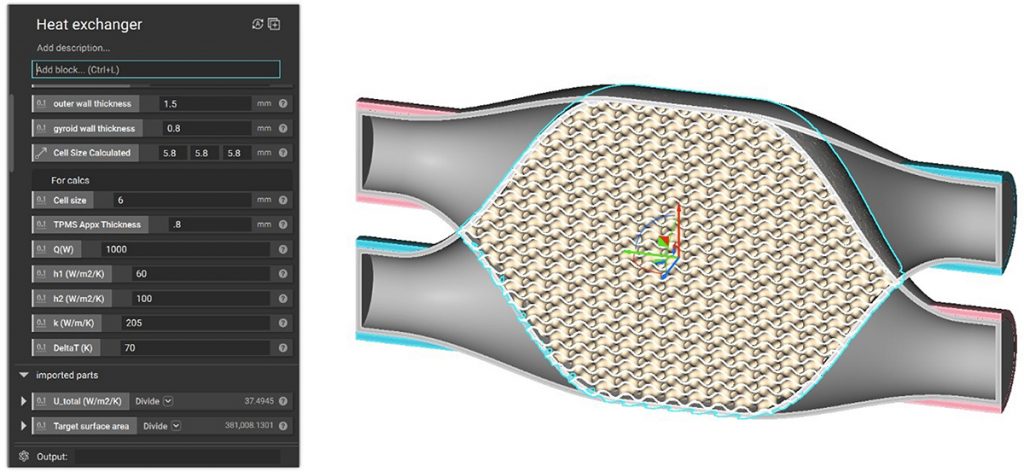

After separating the individual subcomponent bodies, the gyroid-filled lattice space was created. A few heat transfer calculations were used to determine the surface area required to meet the desired conditions. This establishes the optimal gyroid cell size and wall thickness, which are then used to convert the lattice volume into a walled-gyroid TPMS with the proper cell size and wall thickness.

Next, the gyroid structure must be ‘capped’ to separate the hot and cold zones and a solid TPMS volume is created. This represents the gyroid lattice that sits between the previously created gyroid walls. A few more Boolean intersection and union operations cap the cold channels on the hot side, and vice versa.

Finally, a few further Boolean operations are used to combine all the subcomponents into the single ready-to-print heat exchanger. With some basic design-for-AM techniques, it is possible to create extremely complex heat exchangers in which minimal support material is required when additively manufacturing the part.

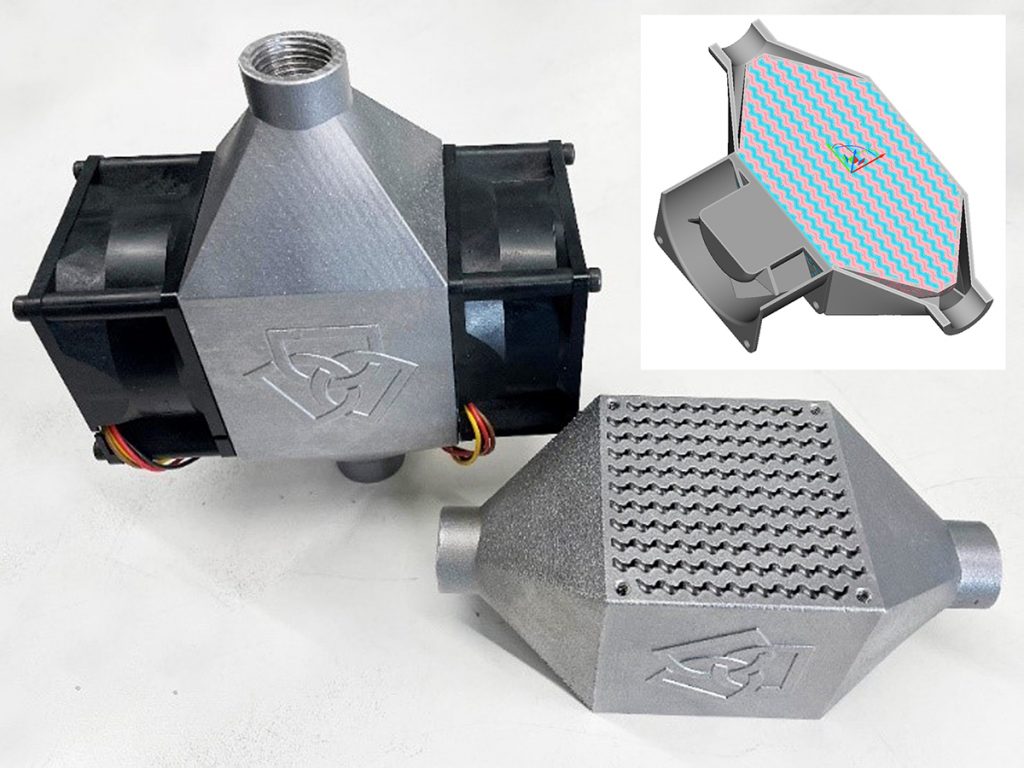

For this heat exchanger, the unsupported angle that is possible was pushed to the limit, with a small amount of support material used to ensure it is manufactured correctly. Support material was only required in areas where removal was easy. Fortunately, the parts were manufactured successfully on the first try.

The initial test was running boiling water through the hot channel and ambient temperature water through the cold channel. A temperature differential of about 65°C (149°F) was achieved. Detailed simulations and more scientific measurements are expected in the future.

Creating the next generation of heat exchangers

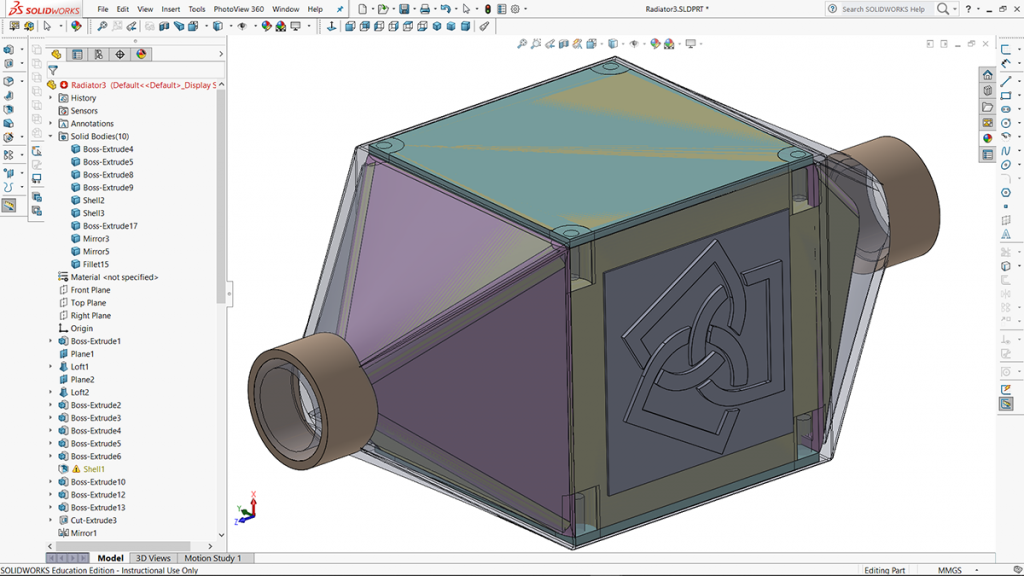

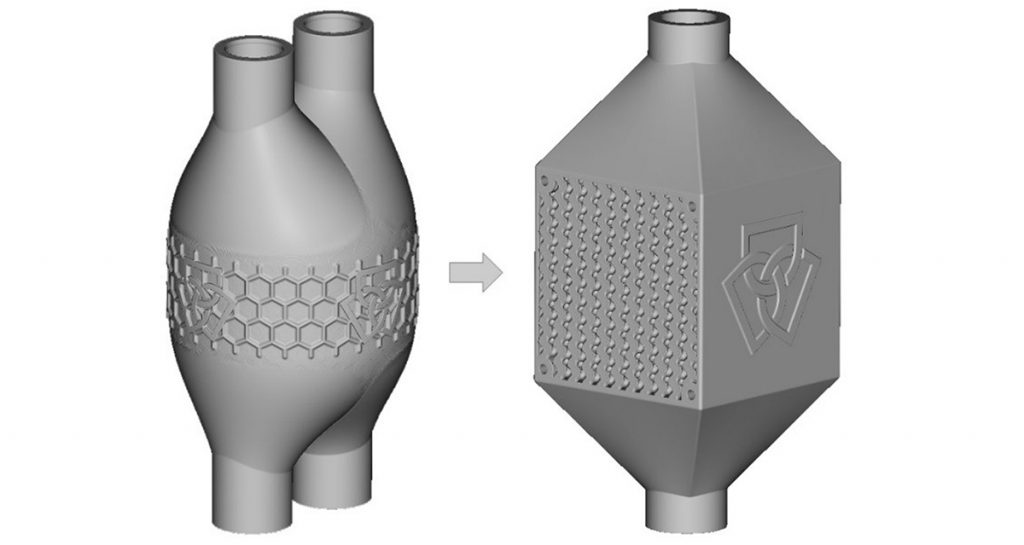

With equation-driven design software, coupled with the proper workflow, one can almost instantly create a new heat exchanger with different characteristics. This makes it ideal for researching more efficient forms of heat exchange. The following example shows the transition from a fluid-to-fluid heat exchanger to an air-to-fluid heat exchanger (a radiator) using a similar workflow.

In summary, once a workflow has been created, it is possible to quickly produce gyroid-based heat exchangers of different sizes and efficiencies. With a few modifications, the workflow can be adapted to create other devices, such as radiators. This project demonstrated the power of gyroids and how they can be used as self-supporting structures to transfer heat from one substance to another. With a large surface area, these designs are excellent candidates for heat exchangers and for creating light-weight self-supporting structures with metal AM.

Author

Olaf Diegel

Wohlers Associates, Inc.

Fort Collins

Colorado 80525

USA