Desktop Metal: A rising star of metal AM targets speed, cost and high-volume production

Over the past few months, it has been hard to avoid hearing about Desktop Metal, Inc. at AM trade shows and in the growing sections of the industrial media. In the following article Terry Wohlers reports on a recent visit to the company’s headquarters. Guided by Ric Fulop, Desktop Metal’s founder and CEO, Wohlers’ initial scepticism is put to rest as he discovers the company’s Studio and Production systems. Together they offer a credible solution to both accessibility to AM technology and the challenges of speed, cost and high-volume production. [First published in Metal AM Vol. 3 No. 2, Summer 2017 | 10 minute read | View on Issuu | Download PDF]

In April this year I visited Desktop Metal in Burlington, Massachusetts, a short distance northwest of Boston. Ric Fulop, founder and CEO, was my host. Prior to my arrival, I knew little about what the company was doing. I had bumped into a number of Desktop Metal employees over the past year and a half, but they were disciplined and shared little detail.

Based on what little I had heard and knew about Desktop Metal’s technology, I was sceptical prior to my visit. What I saw was enlightening. After spending part of an evening and several hours the following day at the company’s headquarters, I could tell it was developing something special that involved considerable invention and innovation. I saw new and creative ideas being applied to hardware, software, materials, sintering and support structure removal. I could tell that many people at the company had been working very hard and a lot had come together to make it work.

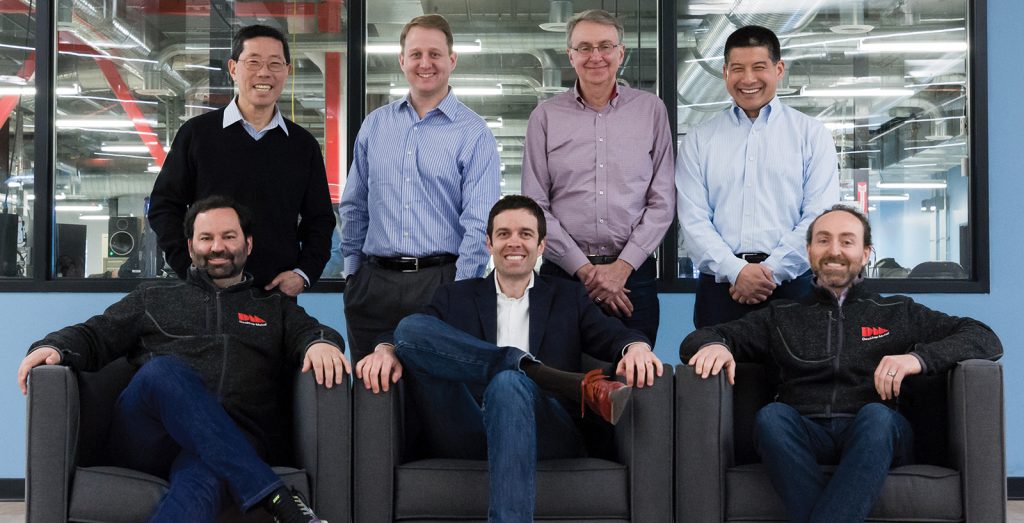

The people

Desktop Metal, like most other high-tech companies, is largely about technology, yet it is as much about people. Organisations need a leader and a figurehead, and Fulop is that person. When going to dinner, Fulop told me that he and Elon Musk, founder of Tesla and SpaceX, have shared some of the same investors, so he had got to know him reasonably well. This led, in part, to the 2017 Tesla Model S that we were riding in. I also learned that Fulop founded A123Systems, which had the largest Boston initial public offering in the past decade. He was an investor in Proto Labs and Markforged, as well as Onshape, a company started by SolidWorks founder John Hirschtick. Fulop is a graduate of MIT, speaks five languages and is a pilot.

The team of people that Fulop has assembled is impressive and represents some of the best minds in materials science, Powder Metallurgy, mechanical engineering, software development, inkjet technology and marketing. I don’t recall a start-up in recent history that has brought together so many accomplished individuals. At the time of writing, the company employed a hundred engineers and fourteen PhDs, including four MIT professors. This talent has led Desktop Metal to 138 patent applications.

Desktop Metal co-founder Ely Sachs invented the MIT binder jetting process made popular by a number of licencees of the technology, among them Z Corp. (acquired by 3D Systems), ExOne (then Extrude Hone), Soligen, Specific Surface and Therics. The printing of pills and tablets by Therics was commercialised by Aprecia Pharmaceuticals in 2016. The FDA provided clearance to Aprecia’s fast-dissolving tablet, making it the first prescription drug made by 3D printing.

On arriving at Desktop Metal’s headquarters I was struck by the openness of the facility. Everyone, including Fulop, was working in the open on tabletops. I saw more than one stand-up meeting, which is often more efficient and productive than conventional meetings in conference rooms. Sofas, easy chairs, table football and ping pong tables contributed to the casual and informal nature of the work space. A catering company brings in food and servers daily for lunch, encouraging employees to stay on-site and spend more time with their colleagues. This approach encourages interaction and helps build relationships – it also saves time. Fulop and I had a stand-up and walk-around lunch, partly due to a plane I had to catch, yet I enjoyed it.

Support removal

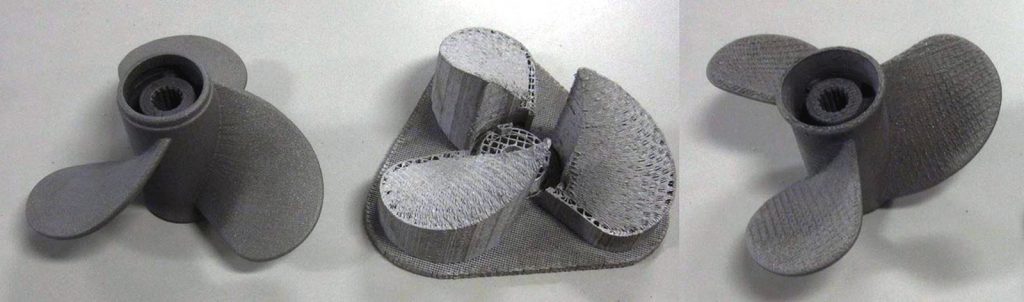

The company has targeted a market which I believe is more than ready for a system that is relatively inexpensive and reduces time, effort and cost in removing support structures, sometimes referred to as anchors. The support removal process is one of the most significant developments at the company. With metal Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) systems, parts are welded to the build plate. Wire EDM, band saws and other tools and methods are used to remove the parts. The support structures must then be removed, which requires hours of additional time and usually a lot of manual labour. This process is also expensive.

The method developed by Desktop Metal is remarkably fast. Ceramic powder is used as an interface material between the part surface and support structures (Fig. 2). The powder is loose, but stays in place. Tapping a part on a bench top is often enough for the supports to fall away from the part. The surfaces where the supports attach to the part are not as good as up-facing surfaces, but are no worse than with PBF (Fig. 3). You almost need to see it or remove the supports yourself to believe it. I saw it twice and then I did it myself.

Materials

Desktop Metal is using metals that are identical to those used for Metal Injection Moulding and is working with AP&C, Carpenter, Sandvik and others for the supply of metal powders. The company produces special rods made up of metal and binder that fit into cartridges for the Studio machine.

Initially, Desktop Metal expects to make thirty materials available, including some of the most popular alloys used in a number of industries. Among them are 6061 and 7075 aluminium, 316L stainless steel, Inconel 625, Ti64, H13 and A2 tool steel, and cobalt chrome. Others include Nvar 36, Kovar F-15, WC-3Co carbide, tungsten chromium and ceramic.

Production speed

Metal PBF systems do not produce parts quickly and system manufacturers are addressing the problem by applying additional energy, such as more powerful lasers and running two or four of them in parallel. This speeds up the process, but it makes the systems more complex and expensive, as well as more costly to operate.

Desktop Metal’s Studio System, expected to ship in September 2017, is targeted at low-volume part production. It produces about 16 cm3 (1 inch3) per hour, which is not fast, but on par with other material extrusion systems. The company’s much larger binder jetting Production System, planned for Q2 2018, is significantly faster. It can process up to 8,200 cm3 (500 inch3) per hour, which is nearly 100 times faster than laser-based PBF systems, according to Fulop. If this holds true, the Production System could turn out to be a workhorse for high volume production of metal parts.

Furnace cycle

Parts produced in both systems are processed in a sintering furnace. Desktop Metal offers a microwave-enhanced furnace that accelerates the heating. The microwave part of the system heats the metal from the inside, while the thermal subsystem heats from the outside. Together, they ramp up the temperature more quickly, provide uniform heating and enhance the microstructure of the metal, Fulop explained.

Depending on the parts and materials used, the furnace cycle can take 2-18 hours. Temperatures range from 600°C to 1,400°C (1,112°F to 2,552°F). The Studio System produces ‘green’ parts that require debinding in the furnace, while the Production System produces ‘brown’ parts, which do not require debinding, thus reducing thermal processing time.

The sintering cycle results in part shrinkage of about 15%. Fulop explained that, as with Metal Injection Moulding, shrinkage is predictable and is taken into account in advance. If this is indeed the case, and customers agree, it should not present a problem for production applications. Geoffrey Doyle, Head of AM Corporate Development at Jabil, explained to me that engineers at his company have positively reviewed the systems from Desktop Metal and they do not view this aspect of the process as a concern. Jabil is one of the world’s largest contract manufacturers with more than a hundred manufacturing plants and 175,000 employees globally.

On several occasions Fulop told me that the process is dimensionally accurate to within 0.2%. This translates to +/- 0.02 mm per 10 mm (0.002 inch per inch). For a dimension that is 330 mm (13 inches) in length, the longest that can be built on the Studio System, one can expect an accuracy of +/- 0.66 mm (0.026 inch), according to Fulop.

Design, engineering and software development

The inside of the Studio machine is cleanly designed. A precision machined metal casting serves as the main chassis for the print heads. In addition to mechanical and electrical engineers, the company employs three full-time industrial designers. I spent some time with them and they know what they are doing. To them, functionality and access to the inside of the machine are as important as product styling and aesthetics.

Rick Chin, a long-time senior employee at SolidWorks and someone I’ve known for many years, heads up software development. He showed me the build preparation software, which is straightforward and provides visual feedback that you normally do not see in other systems. I was also shown some new software that could someday have a significant impact on the way products are designed, but this currently remains confidential.

Commercialisation and roll-out

Fulop has cherry-picked some of the best engineers for Desktop Metal, but it does not stop there; he has also secured strong and experienced people to help market, sell and distribute the company’s products. It is too early to know how the market will warm up to the company and its products, but it looks like Desktop Metal is on the right track.

Fulop stated that both systems are much less expensive to buy, own and operate than the metal PBF systems on the market. The Studio System is $49,900, while the Production System is $360,000. Both systems require furnaces for thermal processing. In the case of the Studio system, a $9,900 debinding unit and a $59,900 sintering furnace are required. I liked the Studio System, but I am most interested in the possibilities associated with the Production System.

Fulop and his team are on to something that could become big. As the saying goes, the devil is in the details, but it looks like they are paying attention to them. In 2016, an estimated 957 AM systems were sold that produce metal parts, according to our research for Wohlers Report 2017. This figure could easily grow to five digits with the availability of AM systems that are much faster and lower in cost to purchase and operate. I am not suggesting that Desktop Metal will achieve this milestone, but Fulop and his team are working hard to be first to produce and ship machines in significantly higher volumes than previously seen.

Author

Terry Wohlers

Wohlers Associates, Inc.

Fort Collins

Colorado 80525

USA

www.wohlersassociates.com

Contact

Desktop Metal

63 Third Avenue

Burlington, MA. 01803

USA

Tel: +1 978 224 1244

Email: [email protected]

www.desktopmetal.com