Researchers develop superalloy to cut carbon emissions from power plants

February 20, 2023

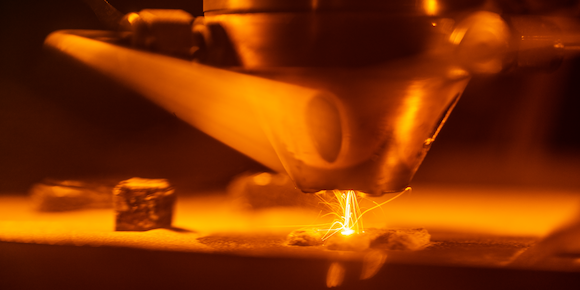

Researchers from Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA, have collaborated with researchers at Ames National Laboratory, Iowa State University and Bruker Corp, to create a new additively manufactured superalloy which may help power plants generate more electricity, whilst producing less carbon. The findings have been published in Applied Materials Today.

The superalloy’s composition makes it stronger and lighter than materials currently used in gas turbine machinery. The researchers have stated that they believe these results could have broad impacts across the energy sector, as well as the aerospace and automotive industries, and suggests a new class of alloys may yet be discovered.

“We’re showing that this material can access previously unobtainable combinations of high strength, low weight and high-temperature resiliency,” stated Andrew Kustas, Sandia scientist. “We think part of the reason we achieved this is because of the Additive Manufacturing approach.”

Per the US Energy Information Administration, approximately 80% of US electricity comes from fossil fuel or nuclear power plants, both of which rely on heat to turn the electricity-generating turbines. Plant efficiency is necessarily limited by how hot the metal turbines can get. If turbines can operate at higher temperatures, then more energy can be converted to electricity.

Sandia’s experiments showed that the new superalloy — 42% aluminium, 25% titanium, 13% niobium, 8% zirconium, 8% molybdenum and 4% tantalum — was stronger at 800ºC than many other high-performance alloys, including those currently used in turbine parts, and still stronger when it was brought back down to room temperature.

Sandia team members used an Additive Manufacturing machine to quickly melt together powdered metals and then immediately manufacture a sample of it. The researchers have stated that the creation of this material represents a shift in alloy development, as no single metal makes up over half of the material. (By comparison, steel is 98% iron combined with carbon and other elements.)

Sandia’s creation also represents a fundamental shift in alloy development because no single metal makes up more than half the material. By comparison, steel is about 98% iron combined with carbon, among other elements.

“Iron and a pinch of carbon changed the world,” Kustas said. “We have a lot of examples of where we have combined two or three elements to make a useful engineering alloy. Now, we’re starting to go into four or five or beyond within a single material. And that’s when it really starts to get interesting and challenging from materials science and metallurgical perspectives.”

Moving forward, the team intends to explore whether advanced computer modelling techniques could help researchers discover more members of what could be a new class of high-performance, AM-forward superalloys.

“These are extremely complex mixtures,” added Michael Chandross, a Sandia scientist specialising in atomic-scale computer modelling, who was not directly involved in the study. “All these metals interact at the microscopic — even the atomic — level, and it’s those interactions that really determine how strong a metal is, how malleable it is, what its melting point will be and so forth. Our model takes a lot of the guesswork out of metallurgy because it can calculate all that and enable us to predict the performance of a new material before we fabricate it.”

Andrew Kustas has noted that there are still challenges ahead, including the potential difficulty in producing the new superalloy in large volumes without microscopic cracks, which is a general challenge in Additive Manufacturing. He also said the materials that go into the alloy are expensive, so, the alloy might not be appropriate in consumer goods for which keeping cost down is a primary concern.

“With all those caveats, if this is scalable and we can make a bulk part out of this, it’s a game changer,” Kustas said.

Alongside the energy industry, aerospace benefits from many of the same qualities which make this superalloy notable. Additionally, Ames Lab scientist Nic Argibay said Ames and Sandia are partnering with industry to explore how alloys like this could be used in the automotive industry.

“Electronic structure theory led by Ames Lab was able to provide an understanding of the atomic origins of these useful properties, and we are now in the process of optimising this new class of alloys to address manufacturing and scalability challenges,” Argibay stated.

“Extreme hardness at high temperature with a lightweight additively manufactured multi-principal element superalloy” is available here, in full.

Download Metal AM magazine