University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers develop novel PBF-LB process that can reduce defects

March 17, 2022

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, USA, have developed a novel Laser Beam Powder Bed Fusion (PBF-LB) process which is said to result in metal additively manufactured parts that have significantly fewer defects, such as pores and cracks.

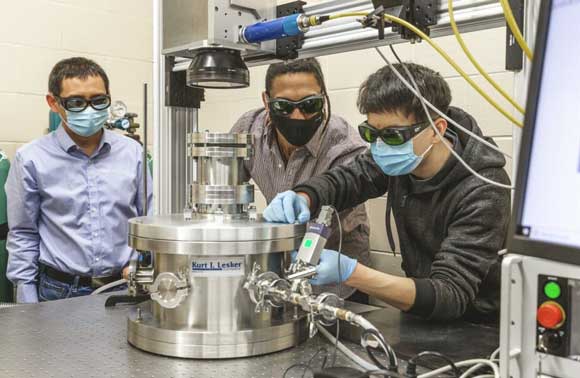

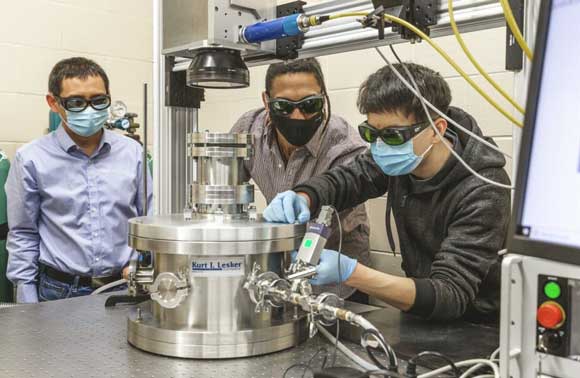

The team, which includes Lianyi Chen, a mechanical engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and doctoral students Luis Escano and Minglei Qu, have had their findings published in the journal Nature Communications. Qu is the lead author of the study and additional authors include Qilin Guo, Luis Escano, Ali Nabaa, S Mohammad H Hojjatzadeh, and Zachary A Young – all graduate students in Chen’s laboratory.

The process uses ceramic nanoparticles to control instabilities during Additive Manufacturing. During the PBF-LB process, the laser melts thin layers of metal powder, the team explains. The material then cools, forming the finished metal part. However, as the laser interacts with the powdered material, the powder surface heats to boiling temperature and creates hot vapour. This vaporisation creates pressure that pushes down on the pool of melting material causing droplets to splash out explains the researchers. These droplets can cause unpredictable defects in the additively manufactured part and droplets also can collide and merge to form a larger droplet, creating more problems in the Additive Manufacturing process and leading to subpar parts.

By coating the metal powder with ceramic nanoparticles, the University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers could control these instabilities. Using both high-speed synchrotron X-ray imaging and theoretical analysis, they found that the nanoparticle coating stabilised the melt pool, preventing liquid droplets from spraying out and forming the larger spatters.

“Using metal 3D printing, we haven’t been able to consistently produce parts with the same high quality and reliability as those made by conventional methods, which means we have big concerns about using 3D-printed parts for critical or load-bearing applications where failure isn’t an option,” stated Lianyi Chen. “This quality problem is the biggest barrier for using metal 3D printing in various applications.”

“We demonstrate a potential way to solve the quality problem by making metal 3D printing technology much more reliable, enabling it to produce consistent, defect-lean parts,” continued Chen. “Using our unique method, we were able to 3D print a metal part that has very few defects and a comparable quality to that of a commercially manufactured part that you could buy off the shelf.”

In addition to the possibilities it holds for Additive Manufacturing, Chen noted that the development could lead to improvements in a broad range of applications, including laser polishing, laser cladding, welding, casting, fluid stability control and more.

“When we introduced the nanoparticles, we found that they made the liquid droplets almost have an armour on the surface, so that when they collided, they didn’t merge together,” commented Minglei Qu. “For the first time, we were able to get rid of the problematic large spatter.”