GE sees potential in ‘self-inspecting’ metal Additive Manufacturing systems

October 27, 2017

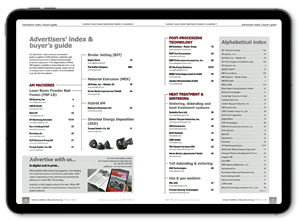

The view inside an AM system’s build chamber (Courtesy Concept Laser)

General Electric (GE) reports that researchers at its Additive Research Lab, GE Global Research, Niskayuna, New York, USA, are working to combine computer vision and machine learning to develop a type of metal Additive Manufacturing system with the ability to self-inspect its manufacturing process in real-time.

According to GE, the eventual goal of the project is to build a system which can achieve ‘100% yield’ – wherein a machine only produces perfect parts, eliminating the need for post-processing and inspection.

Some large and complex parts, in particular those produced by GE Aviation, can take days or weeks to produce by metal Additive Manufacturing. Where post-process inspection is the only validation method available, errors and faults in parts may only be discovered after this extensive build-time.

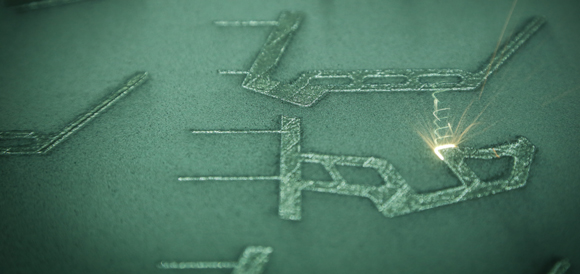

An aerospace part produced by GE subsidiary Avio Aero (Courtesy Avio Aero)

A number of factors can contribute to sub-optimal build results in metal Additive Manufacturing. Among them are variations in powder particle size, the way new powder layers are added and potential property changes arising from powder reuse.

GE has previously applied its computer vision technology to areas such as the study of diseased tissues and the detection of microscopic cracks in machine parts, and stated that it will now use it to detect potential errors during manufacture.

“We do a tremendous amount of work on additive powders to understand what characteristics lead to a good build,” explained Kate Gurnon, a member of GE’s research team. “We want to apply this automatically to machines and, in real time, observe the dynamic behaviour of the powder delivery to the build plate. In this way, we will have a better chance of getting to the 100% yield, faster.”

The team will then attempt to ‘teach’ machines which types of powder behaviour correlate with part defects. “Using artificial intelligence and machine learning, we will turn 3D printers into essentially their own inspectors,” stated Joseph Vinciquerra, who runs the Additive Research Lab.

“By eliminating the need to inspect parts after they’re completely built, we can shave days, even weeks off the entire manufacturing process and lead to a breakthrough in productivity.”

The team reports that it has been ‘teaching’ its AI how to make the correlation between manufacturing error and defect by first additively manufacturing simple geometric shapes such as flat bars and cylinders from metal, and using high resolution cameras to film every layer and record streaks, pits, divots and other patterns in the powder which would be almost invisible to the naked eye. Next, each sample is run through a powerful CT scanner and any internal flaws recorded.

Using the resulting data, a proprietary machine-learning algorithm correlates the internal defects revealed during the CT scan with the powder patterns recorded by the high-resolution cameras. According to Vinciquerra, the more often this process is carried out, “the smarter the system gets. The computer vision alone will eventually have enough training to tell us whether we are going to have a problem.”

The proposed AI would be able to use computer vision to spot familiar powder patterns in the machine and correct the build parameters in real-time (Courtesy GE Reports)

Once it has the required training, GE reportedly plans to integrate the AI into Additive Manufacturing machine controls. This AI would be able to use computer vision to spot familiar powder patterns in the machine and correct the build parameters in real-time to eliminate potential errors. For example, if the AI were to detect a streak which may lead to cavities in the final part, it could automatically add more power or speed to the laser beam to adjust or change the thickness of the next layer.

“The idea is that the machine has a compensation strategy based on what the computer vision sees,” Vinciquerra stated.” Another step which GE’s research team believes may help it achieve this goal is the building of a ‘digital twin’ – a virtual representation of the production process which compares ideal conditions with reality, in real-time, and suggests changes to achieve the perfect result. The digital twin “represents the gold standard of how the material should be processed,” explained Vinciquerra. “It’s telling me that if I use these parameters to build a part from a certain material, I can expect this kind of behaviour in the final product.”

GE stated that the next generation of its digital twin will be able to gather computer vision data as well as collecting information reported by other build-monitoring sensors, such as the shape of the melt pool.