SINTEF project aims to advance Additive Manufacturing adoption in maritime sector

February 1, 2022

Over the last three years, Norwegian Research and Development partner SINTEF has been involved in FlexiMan, a collaborative European research project focused on the potential of Additive Manufacturing to make the maritime industry more efficient and sustainable. The project partners are Nordic Additive Manufacturing AS, Kongsberg Maritime AS, Fraunhofer IPK, LaserCladding Germany GmbH and Mecklenburger Metallguss GmbH.

The notion of a circular economy characterises the thinking behind the project; the goal is that the material of damaged components, or parts of the damaged components, should be reusable. As well as being sustainable, by additively manufacturing these parts at the point of need, it also minimises required storage space and removes the cost inherent in shipping over long distances.

“If we succeed, this will give suppliers to the shipping industry a great advantage in an industry with fierce competition and high demands on profitability,” stated Afef Saai, project leader on FlexiMan. “In addition, we use only the materials that are needed. Nothing goes to waste.”

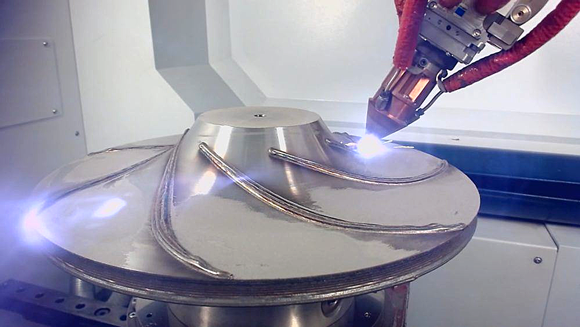

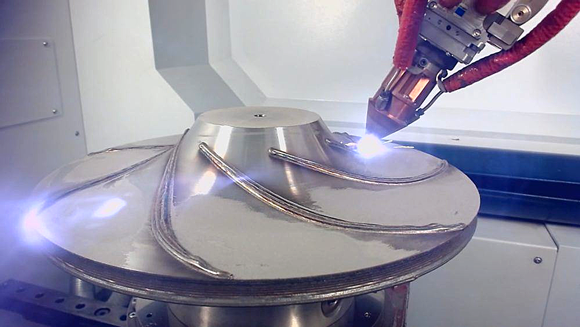

In one example, the team was in charge of an impeller whose blades were worn. Normally, this would result in the entire impeller being discarded. As part of the FlexiMan, the team instead additively manufactured new alloy blades onto the impeller so that its functionality can be maintained for longer. And when a component is so broken that this sort of repair isn’t viable, the part can be broken down into raw material so that it can be used to manufacture entirely new parts.

Compared to traditional machining, AM allows for more customised component solutions. A type of hybrid material solution is one such option: When a part is very large and has areas not as susceptible to wear, the cheaper option of using ordinary steel is possible; the smaller parts which see the most exposure be additively manufactured in more expensive, high-quality materials.

Another advantage is that you can limit the use of materials on large and heavy parts. An example is the propeller, here the scientists have a plan to develop a hollow variant. This means that less of the material can be used, that the propeller becomes lighter and thus requires less fuel. But at the same time, scientists need to know that it is strong enough.

While other large-scale industries such as aerospace and automotive have already seen the adoption of AM, the stringent maritime guidelines have been a barrier to ready adoption in that sector. SINTEF locations in Trondheim and Raufoss are currently testing manufacturing procedures that fit into these guidelines; the components tested so far include a jet impeller along with an attached pump and separate ship propeller.

“Now it has become possible to print this [jet impeller lid] in one piece instead of machining three different parts that then need to be assembled together. On top of that, we can now make thirty such valves at the same time,” stated Mette Nedreberg, Chief Engineer and Materials Technologist at FlexiMan partner Kongsberg Maritime.

“With 3D printing,” she continued, “we can obtain parts ourselves when the order arrives and can thus reduce the need to have parts in stock. We also see that in the future when maintenance work is carried out, we can make spare parts on board or in a port near the vessel where Kongsberg equipment is installed. It’s a win-win for all parties.”