Ricoh develops Binder Jetting process for aluminium part production

December 1, 2020

With metal Binder Jetting (BJT) systems now offering the potential for the high-volume, cost-effective Additive Manufacturing of complex parts, there is a growing demand to broaden the range of material options available. Aluminium is one such metal that could offer the potential to produce a variety of new parts; however, the metal can be difficult to process in the sintering stage.

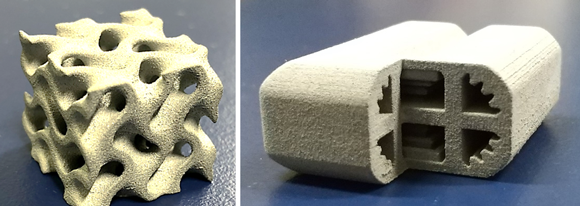

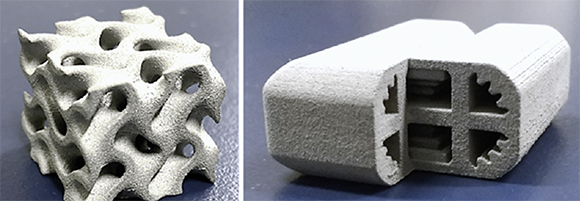

To alleviate this problem, a team of researchers at Ricoh Company Ltd, based in Kanagawa, Japan, has developed a unique binder material that, when combined with a suitable debind and sinter stage, offers the potential to use typical aluminium powders in the Binder Jetting process. Furthermore, the use of a liquid immersion technique developed at Ricoh for removing excess powder is said to make it possible to form complex internal channels during the process – an option the company says is not possible with conventional processes (Fig. 1).

For the development of this new binder system, the team used an AlSi alloy powder with an average particle size of 35 µm, coated with what is described as a resin. The main objective of the resin coating, explains Ricoh, is to allow bonding through a mutual interaction with the binder liquid, as well as reducing the risk of explosion. The binder liquid used incorporates an organic solvent and an additive to ensure the cross-linking of the resin-coated powder particles.

Ricoh used a prototype Binder Jetting machine, developed in-house, to create a powder layer thickness of 84 µm with a binder liquid drop resolution of 300 x 300 dpi. The resulting green body was said to be resistant to specific solvents due to the cross-linking. Immersing the parts in a solvent for a set time therefore enables the efficient removal of excess powder, particularly from small internal channels.

Following a solvent drying stage, the parts undergo a liquid-phase sintering operation. A target liquid phase amount of approximately 20–30% is required, with the parts maintaining a temperature appropriate for elution of the liquid phase amount for between two and five hours.

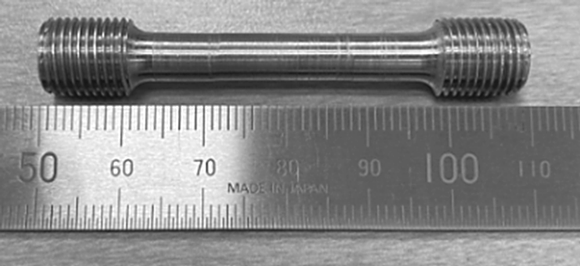

The researchers reported that tensile strength testing, thermal conductivity testing, cross-section structure observation, and X-ray CT internal observation were performed on the resulting sintered parts. The tensile strength and stretch values of the test sample seen in Fig. 2 were reported to be 100 MPa, equivalent to that of a typical pure aluminium material. Using a xenon flash analyser, thermal conductivity was determined to be 188 W/mK, equivalent to AlSi die-cast products.

An X-ray CT image of a sintered block, measuring roughly 15 mm per side, is shown in Fig. 3. The sample’s relative density reached 98.4%, and it was confirmed that sintering was accomplished well, with no large pores. The results of microstructural observations (Fig. 4, overleaf) found that grain sizes were approximately 50 µm, equivalent to a typical cast structure.

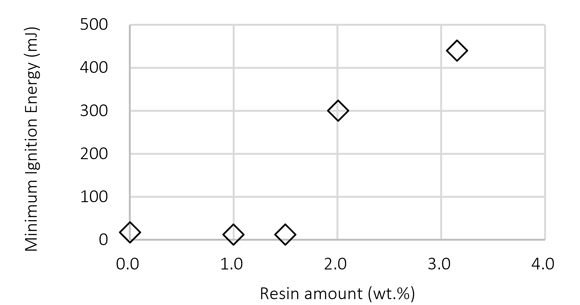

The relationship between the amount of powder coating resin and the minimum ignition energy is highlighted in Fig. 5, showing that when the resin amount exceeds 2 wt.%, the minimum ignition energy increases, greatly stabilising the coated powder in comparison to uncoated powder. The researchers state that the resin coating appears to suppress the transfer of explosive energy between particles.

This testing confirmed that it was possible to form 90 mm long internal channels with diameters of 2 mm. The company states that it is now working on the creation of a prototype with a larger build chamber and even thinner internal channels. The team is also working to expand the range of alloys that this method can be used with.