Empa uses novel Additive Manufacturing process to alter properties in magnetic parts

June 15, 2020

Empa, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology based in Dübendorf, Switzerland, has published its results from a recent research study, creating new alloys with novel properties and embedding them in additively manufactured metal workpieces with micrometre precision.

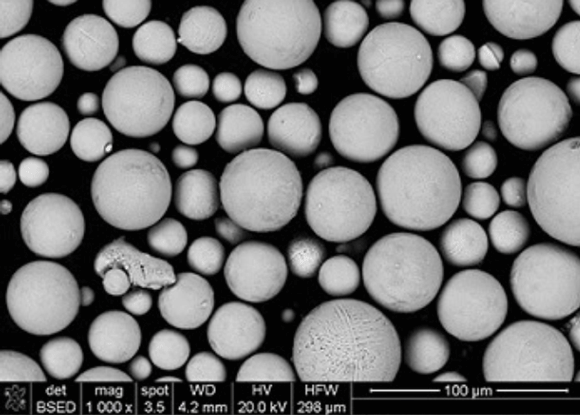

During metal Additive Manufacturing in laser-based machines, temperatures of more than 2,500℃ are reached within milliseconds, causing some components of the alloys to evaporate. Widely considered a problem inherent to the process, Empa researchers explain that they have transformed this problem into an opportunity..

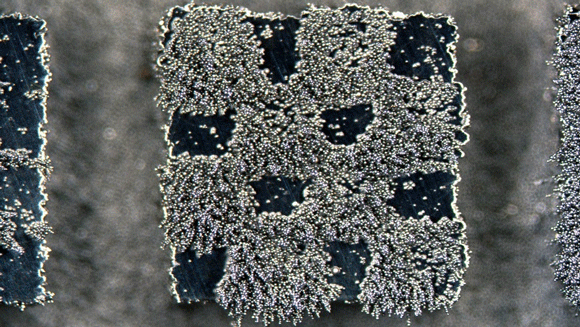

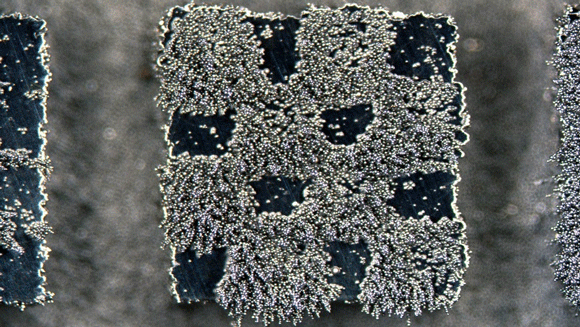

Empa states that the material sample, which it describes as a small metallic chessboard 4 mm long on either side, shows that Additive Manufacturing is not only suitable for creating new geometric shapes, but also for producing new materials with completely new functionalities. The small chessboard is a particularly obvious example, with its eight magnetic squares, and eight non-magnetic squares. The entire piece has reportedly been additively manufactured from a single grade of metal powder with only the power and duration of the laser beam varied.

At the beginning of the study, the Empa team, led by Aryan Arabi-Hashemi and Christian Leinenbach, used a special type of stainless steel which was developed twenty years ago by Hempel Special Metals in Dübendorf, among others. The so-called P2000 steel does not contain nickel, but around 1% of nitrogen. P2000 steel is said to not cause allergies and is well suited for medical applications, however it is particularly hard, which makes conventional milling more difficult.

Initially, it seems unsuitable as a base material for AM, state the team. In the melting zone of the laser beam, the temperature quickly peaks and a large part of the nitrogen, within the metal normally evaporates, changing the properties of the P2000 steel.

Arabi-Hashemi and Leinenbach are reported to have turned this drawback into an advantage. They modified the scanning speed of the laser and the intensity of the laser beam, which melts the particles in the metal powder bed, and thus varied the size and lifetime of the liquid melt pool in a specified manner.

In the smallest case, the pool was 200 microns in diameter and 50 microns deep, in the largest case 350 microns wide and 200 microns deep. The larger melt pool allows much more nitrogen to evaporate from the alloy; the solidifying steel crystallises with a high proportion of magnetisable ferrite. In the case of the smallest melt pool, the melted steel solidifies much faster. The nitrogen remains in the alloy; the steel crystallises mainly in the form of non-magnetic austenite.

During the experiment, the researchers had to determine the nitrogen content in tiny, millimetre-sized metal samples very precisely and measure the local magnetisation to within a few micrometres, as well as the volume ratio of austenitic and ferritic steel.

According to Empa, the experiment could soon add a key tool to the methodology of metal production and processing. The method is said to be not limited to stainless steels, but can also be useful for many other alloys.

“In 3D laser printing, we can easily reach temperatures of more than 2500℃ locally,” stated Leinenbach. “This allows us to vaporise various components of an alloy in a targeted manner – e.g. manganese, aluminium, zinc, carbon and many more – and thus locally change the chemical composition of the alloy.”

Leinenbach considers certain nickel-titanium alloys known as shape memory alloys and at what temperature the alloy “remembers” its programmed shape depends on just 0.1% more or less nickel in the mixture. By using AM, structural components could be made that react locally and in a staggered manner to different temperatures.

The ability to produce different alloy compositions with micrometre precision in a single component could also be helpful in the design of more efficient electric motors, explains the Empa. It is now possible to build the stator and the rotor of the electric motor and make better use of the geometry of the magnetic fields.